I was born and raised as a feminist by my mother, who is exactly 40 years older than I am. My mother went to college in the 1960s in New England, where she tried to open a bank account but they wouldn’t let her unless her husband or father co-signed as an account holder. She wasn’t legally allowed to have a credit card until 1974. She got married in 1975, and legally, she had no right to refuse to have sex with her husband until the late 1970s in some states (and 1993 in others).

The Pill was introduced in 1960, but she couldn’t legally use it if she wanted to – it wasn’t until 1965 that the Supreme Court ruled married couples had a constitutional right to possess it, and wait, she wasn’t married yet – it wasn’t until 1972 that the Supreme Court ruled unmarried people also had a constitutional right to possess it. Then, of course, there was 1973’s Roe v. Wade, protecting a woman’s right to an abortion before fetal viability, though my mother told me often she’d never exercise that right.

My mother was told by her high school guidance counselor that there was no need for her to go to a four-year college, because she was “pretty” and she’d certainly find a husband. She went to college anyway. She also got married and raised three children – I was born in the 1980s.

-

Mum & I, 2011.

I’m an American woman who has never been legally denied those rights above as a result of my gender. That doesn’t mean I don’t experience gender discrimination or sexism or harassment, but at least it isn’t codified by law anymore.

Yet I still cling to the word “feminist”. I’ve used it often to describe myself and more than once I’ve heard someone scoff in response with about as much derision as I use when I hear someone use the term “9/11 Truther”.

“Feminist” has become a dirty word in many circles and it bothers me. Not just because I still believe in what the word means to me, but because I also understand why so many people don’t like it. I understand that some feminists are very hostile. I also understand why they are. I understand that some men feel hurt by the implication that they (as a gender) haven’t been good to women, even if they themselves (as an individual) have been.

I understand the opposition to the term “war on women” – heck, I’m a feminist who hates the phrase because I think dividing the masses into warring factions is a way of distracting from the real problems of power systems. I understand the dislike of describing current American society as “patriarchy”; I even reduced my use of the term, because it doesn’t seem to carry the nuance of a society where power is generally held by few, and both genders suffer under it.

Now, for the record, despite living in a time and place where I am not legally denied the rights I previously mentioned as a result of my gender, I am acutely aware of how close that time was. I often feel like people don’t realize how close.

My mother lived through a time where she was legally inferior to men. That hits home, and makes me tremendously grateful to those women who advocated against law, against tradition, against the common thoughts of the day – that they had a right to their money, their bodies, and the direction of their lives. Thus, my affection for the term “feminism” remains, and I remain inside the movement, believing it to be a liberation philosophy, and I support the aspects of it which reflect that goal.

Many people tell me that if women are no longer legally inferior to men, the feminism fight is over. That there is no need to continue this movement to liberate women from laws that no longer exist. They tell me my rights to birth control and abortion are achieved and I am not in danger of losing them. They tell me I’m being collectivist or sexist because I’m focusing on my gender, possibly to the detriment of the liberty of the other gender.

I hear them. I consider them. I seriously, seriously do.

So here’s another story of women’s rights, this time, in Afghanistan.

In 1941, the first secondary school for women was opened in Kabul. In 1959, women were officially allowed to unveil. In 1964, women were given the right to vote. Note: Afghanistan had cities like Kabul and also rural areas; often women were still treated as property in rural areas. But things were improving, generally, for women there.

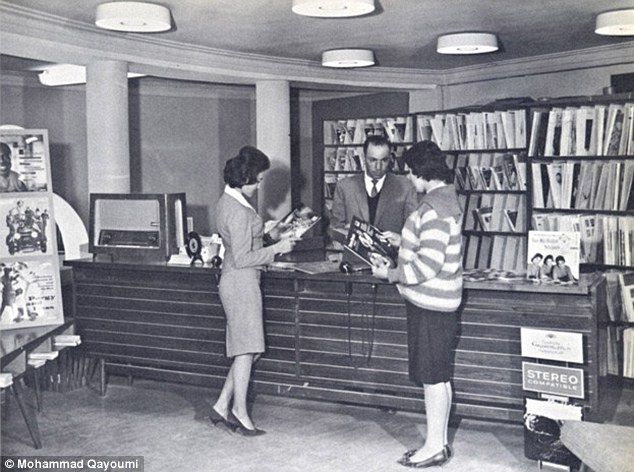

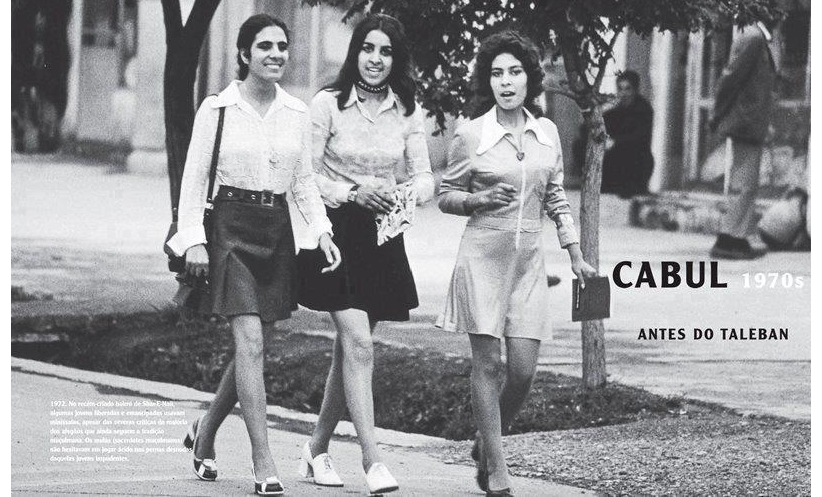

Here are two pictures of women in Afghanistan in the 1970s:

Things were very different than what we typically visualize for that region. Massive social reform happened in the 1970s & 80s, as Soviet Russia supported various parties within Afghanistan. Bride prices were abolished. Girls couldn’t be married under the age of 16. Women were able to go to school, some were doctors and professionals.

In 1979, the United States Central Intelligence Agency began covertly funding and organizing Operation Cyclone, a program to finance and arm the Afghan mujahideen against the Soviets. President Reagan greatly expanded this program, which lasted over ten years and cost billions of dollars. Following the exit of the Soviets in 1989, things were pretty tense in Afghanistan for women, but up until 1995, women were half the working population in Kabul.

The mujahideen became the Taliban. In 1996, the Taliban took over Afghanistan’s capital, and with that, restrictions were immediately imposed. Women were forbidden to leave the house without a male escort, forbidden to work, forbidden to seek medical help from male doctors (and female doctors were outlawed), and were forced to cover themselves entirely.

I don’t think I need to tell you how the Taliban was allied with al-Qaeda, which was responsible for a little thing we call “September 11th”. I don’t need to spell out the details of how in 2001, we started bombing the people we were funding 20 years earlier, and fighting for the re-liberation of a people who we helped oppress two decades prior. I digress.

Afghan women are now re-involved in education, the workplace, politics and more, though they often live in fear of violence as a result of simply being free to do these things I take for granted daily. Thanks to American efforts to end the influence of Soviet Russia, we helped set back women’s rights in Afghanistan by a generation.

Now… do I think that conservative Christians are going to pull a Taliban on American women? No.

Do I think I’m seriously at risk of being housed under sheets that cover every inch of my skin while being beaten for leaving my home without an escort? No.

Do I cry when I realize that women my mother’s age, experiencing the opportunities of voting, education and the sorts of freedoms she was also experiencing suddenly had those freedoms taken from them and their daughters did not grow up free like I did? Absolutely.

I’m aware that for all the rape culture and patriarchy commentary in my own country, for every man who feels entitled to sex from a woman, and for every instance of legislation against my body here in America, there are women all over the world who are killed for trying to go to school. There are women who are raped who are then expected to either marry their rapist, or be killed for their “impurity”. I’m aware that around 125 million women have undergone female genital mutilation.

I am profoundly grateful to live where I live in the time that I live in. It gives me awareness of freedom and where it is lacking. My government does not actively silence my words. I am armed with knowledge, perspective and a voice in a battle against oppression.

Now, as someone who considers myself libertarian, and considers libertarian feminism a real and important movement – I have to ask myself what I can do about women all over the world who don’t experience the freedoms that I get to.

I don’t advocate force, so I can’t advocate war to liberate them. Even if I did, I also see that fighting wars against other oppressive governments (like Soviet Russia back in the 80s) can massively affect the freedom of people in a completely different country. In the meantime, I feel silly complaining about street harassment when I know what these women go through, though that doesn’t make it okay.

But as a libertarian I know that freedom means responsibility. I have to be ever vigilant about my government and my society, so it never falls to something so horrible and oppressive. I need to watch for any signs that it could, for any reason, much like I keep an eye on every social outcry that may result in big government “solutions”. I need to oppose these things. I need to be aware of and supportive of movements of liberation around the world – I can donate to international organizations or send words of support to women fighting wars, daily, for their dignity and humanity.

I am a feminist because of the Taliban and religious extremism. I am a feminist because of people like Elliot Rodgers. I am a feminist because of every person who told my mother “no” when she tried to be an independent self-possessed woman with her own money, her own education and her own life.

I am a feminist because of every person who tells me I don’t need feminism. I am a feminist because of every person who calls themselves anti-feminist, as if there hasn’t been social and legal oppression of women throughout the world. I am a feminist because of people who tell me feminism had nothing to do with the difference between my mother’s experience and mine. I am a feminist because of what “patriarchy” does to oppress boys as well as girls.

I am a feminist because of feminists who make me ashamed of being a feminist, because I want the word to mean liberation like it should, and I’ll work every day to make that the case.

I am a feminist because I believe the world is better when women are liberated, when they can stand equally beside men to fight for everyone’s liberation from oppressive social structures and oppressive governments.

I am a feminist because I have the freedom to be one. I am a feminist because I’m a product of feminism, and I am profoundly grateful for that.

5 thoughts on “I’m A Product of Feminism”

Comments are closed.